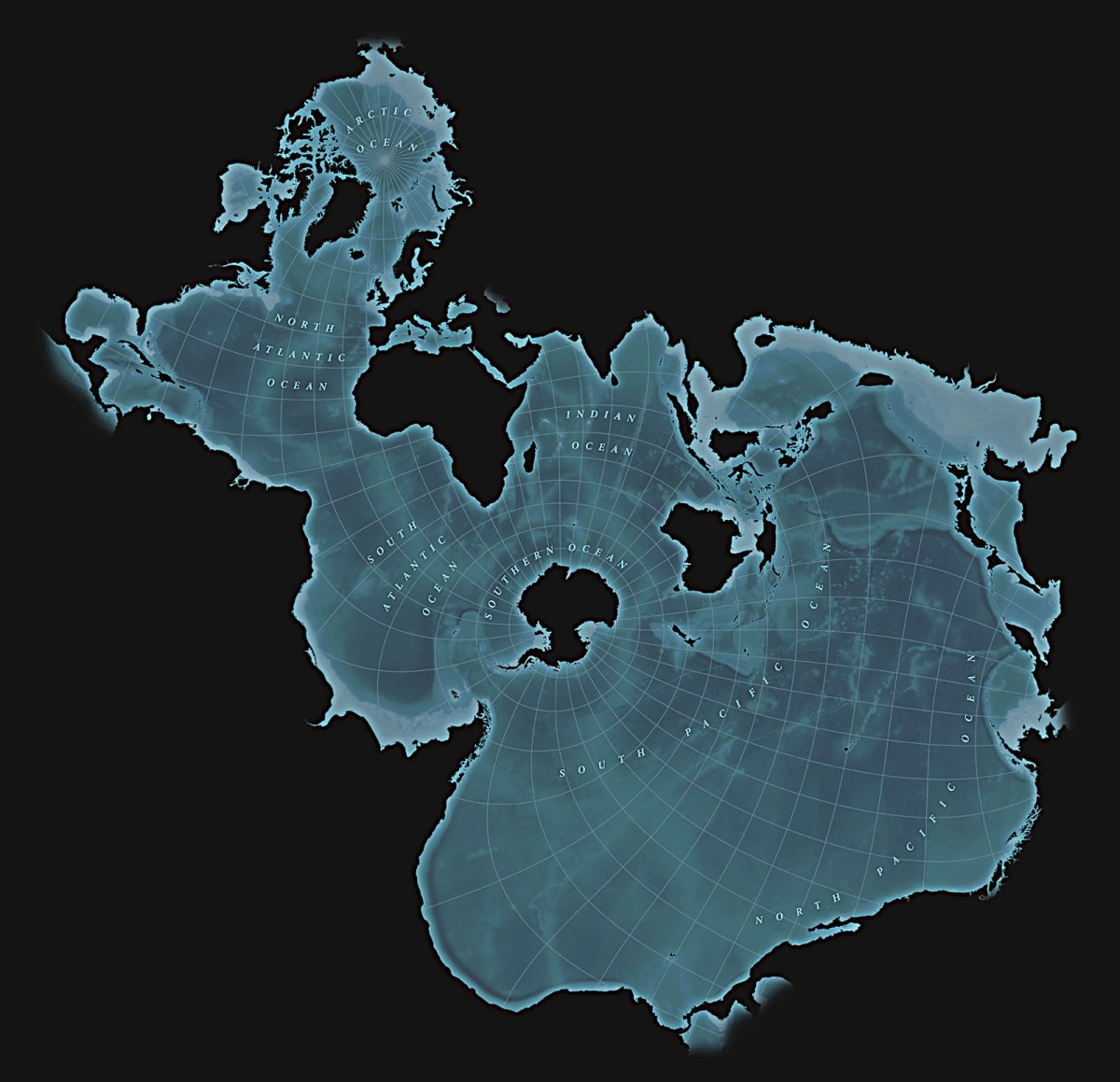

Image: Wikimedia

Science and technology – 3

< Previous | Index | Next >

We’ve just had a heat pump system installed in our home and it is so, so different from the old, gas-fired boiler that used to keep us warm in winter. I’ll give you some details about it in another article. But the main reason I’m writing is to explore what it means to be migrating towards clean, green energy; and what it means if we fail. But before we can focus on any of that, we need to understand where our energy comes from and where it goes.

Primary energy sources

We all use energy every day, as a species. And just like all other forms of life, that energy comes almost entirely from rearrangements within atomic nuclei. There are two ways this can happen – nuclear fusion and nuclear fission. Fusion is what happens in the centre of the sun where hydrogen atoms are combining to form helium, releasing a lot of heat in the process. Fission is what happens suddenly in a nuclear bomb or slowly in a nuclear reactor. Heavy atoms fall apart and release energy as they do so. The rule is that heavy elements release energy if they break apart (fission), while light elements release energy if they join together (fusion). Elements in the middle mass range around iron don’t break apart or join together easily and produce little or no energy if forced to do so. Indeed, sometimes these elements might require energy.

The sun’s energy comes from fusion in the core and is eventually released as sunshine. Sunshine heats the Earth’s surface and winds are caused as air masses expand or contract due to temperature changes. Waves, in turn, are caused by wind crossing water surfaces.

Some of the Earth’s inner energy comes from the spontaneous fission of heavy elements in the core and mantle, and some is remnant heat from Earth’s formation 4.5 billion years ago; that core energy is released in the form of volcanoes, earthquakes, and hot springs.

Tidal energy is the final source we need to consider. This is the result of gravitational forces from the Sun and Moon causing bulges in the oceans, the Earth revolves daily beneath these ocean bulges and the water depth varies as the state of the tide changes throughout the day.

It’s also gravitational contraction that gets the centre of a star dense enough and hot enough for fusion to begin in the first place. That’s it for primary energy sources. All of these count as green energy as none of them release carbon dioxide.

We can collect solar or wind energy, for example, with a clear conscience, also geothermal energy, hydroelectric power, hot springs, tidal power, or nuclear. There may be issues with all of these, but none of those issues have anything to do with releasing greenhouse gases.

Plants and animals

Everything else is what I call secondary or tertiary energy. Plants (secondary) trap some of the energy in sunlight and use it to grow and to store in chemical form. And animals (tertiary) obtain energy by eating plants or other animals. These too can be counted as green. The natural world runs on light from the sun, and all the carbon dioxide released is balanced by the light trapping mechanism of plants that uses carbon dioxide from the air and water from the ground and releases oxygen. The carbon is used to create the structural elements of wood and all the living tissues of plants and animals. Most of this is recycled naturally by decay within a few years or decades, and the carbon balance of the Earth doesn’t change. Except sometimes carbon containing materials were trapped long term in geological deposits of coal, oil and natural gas. This sequestration of carbon compensated for the continual, slow warming faced by the planet as the sun increased its output of light and heat over geological time.

Deep time

All stars grow brighter and hotter as they age, a perfectly natural and well understood process that we don’t need to consider here – except to mention that it happens. Rising temperatures cause shifts in a planet’s climate, and if it goes far enough a planet can become very hot, lose its water to space, and become a roasting desert like Venus.

This did not happen to the Earth because the continual, slow removal of carbon from the surface kept carbon dioxide levels low and significantly reduced the greenhouse effect.

Early human technology

Early human technologies did not involve the use of coal, oil or gas. When fire was first discovered and tamed for human use, the only fuels were wood and various kinds of plant and animal oils and fats. Our technology remained green, using only recently captured energy.

But around 4000 years ago, people began to discover surface deposits of coal and oil. The Romans and the Chinese knew of coal and used it on a small scale as a fuel.

We were still remaining green on the whole. The industrial revolution began with water power to mill grains, process wool into cloth, and so on. The first industrial towns were always built in valleys where there were rivers of sufficient size to power the machinery. Up to this time it’s difficult to find much change in atmospheric carbon dioxide levels in, for example, ice cores or ancient timber. When carbon fuel was needed for processes needing extreme heat (eg iron smelting, pottery firing), charcoal was used; this was made by incomplete burning of wood in an oxygen poor environment.

But then came steam power!

Advancing industrial growth

It soon became clear that charcoal was not available in sufficient amounts to be a suitable fuel for burgeoning industry. Instead, coal began to be mined in ever-increasing quantites to feed iron and steel works, power pumps to move water from mines, and more and more to power transport. Railways and shipping consumed ever larger amounts of carbon in the form of coal. Oxygen was consumed and carbon dioxide released – and at that point the human race started on a dangerous path towards climate change. At first the increase in carbon dioxide levels was imperceptible and so was the increase in average temperatures.

And that is where we were 100 years ago.

Oil is not mainly carbon, like coal. It has almost two hydrogen atoms to every carbon in its structure so it’s slightly more green than coal. Hydrogen oxide (aka water) is a less powerful greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide. Gases are even better than oil, methane is best of all as it contains four hydrogens to every carbon.

But to be fully green we must move all our energy production to solar, wind, nuclear, and tidal energy supplies. There are financial incentives to make the move too. To burn coal, oil or gas at a power station you must construct the power plant and transmission lines and then continually buy the raw materials to burn to generate power.

Wind turbines, solar panels and hydro also involve building infrastructure, but the fuels to run them – sunshine and wind – are free. This makes the energy they supply to the power grid much cheaper than energy from non-green technologies.

The economical costs of mining or drilling, as well as the health and environmental costs of emissions from non-green energy sources renders the move to greener energy an absolute no-brainer. And that’s before we start to take into account the serious risks of a warmer climate. These include rising sea-levels; unlivably high temperatures; heavier and unpredictable rain; forest fires; spreading of deserts; and harsher and more frequent cyclones and hurricanes. All of these horrors are already with us and are worsening year on year by larger and larger amounts.

Back-pedalling furiously cannot save us now. But it’s not too late to moderate the damage, eventually stabilise the problems we face, and see a gradual return to what was once normal. But we absolutely must act now, the longer we leave it, the worse it will get.

See also:

< Previous | Index | Next >

Useful? Interesting?

If you enjoyed this or found it useful, please like, comment, and share below. (If you don’t see those links, click the article’s title above the main photo and they will appear.) Send a link to friends who might enjoy the article or benefit from it – Thanks! My material is free to reuse (see conditions), but a coffee is always welcome and encourages me to write more often!

![]()